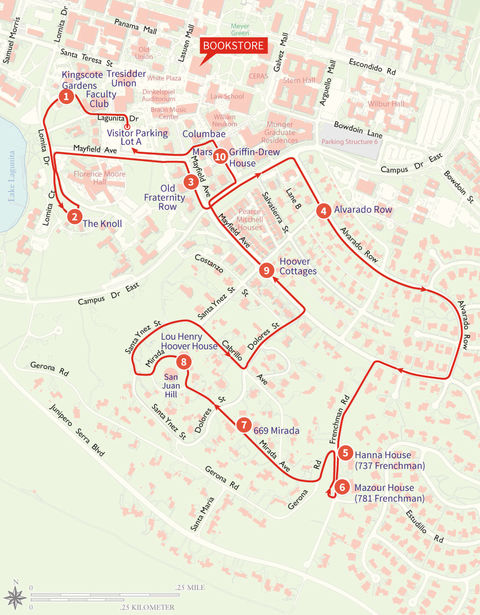

Hike C-10: Noteworthy Residences Loop

18 Themed Walks Exploring the Stanford Campus, 20 Local Hikes from the Foothills to the Bay

Written by Tom DeMund, Walking the Farm is rooted in the Bill Lane Center for the American West’s annual tradition of hiking the Stanford campus and its environs to trace the links between the university, its founders Leland and Jane Stanford, and the dynamic region it helped shape. From the transcontinental railroad to postwar atomic research, and onward to the rise of Silicon Valley, walk in the footsteps of generations past.

Directions to the Starting Place

I’m going to direct you to Public Parking Lot A. However, this lot fills up rapidly most weekdays and even on Saturdays with little turnover. Hence, if you find the lot full, you can drive around and around, along with others doing the same thing, trying to be at the right spot when someone pulls out. (Why is it another site-searcher always seems to just beat me to the emptying parking space?) If you’re lucky enough to get a space, pay at the nearest kiosk. Note that parking on weekdays after 4:00 p.m. and all weekend long is free. Hence, Saturday or, better yet, Sunday might be good days for you to do this loop. If you give up on Lot A, consult Appendix C for alternative choices. If you park elsewhere, then you’ll have to consult the Appendix C map on how to get back to my description’s starting place.

To get to Parking Lot A from the intersection of Palm Drive and El Camino Real, drive toward the Main Quad on Palm Drive, turning left in .5 mile onto Campus Drive, which becomes Campus Drive East. Continue on it for 1.2 miles, passing where it bends to the left then to the right. A couple of blocks after the right bend, you’ll encounter a stop sign at Mayfield Avenue. Turn right onto Mayfield, which soon makes a left turn. In half a block, you’ll find Parking Lot A on your right. Good luck.

First, let me admit that this chapter can’t begin to compare with the marvelous work done by the Stanford Historical Society, whose research and publication of the six-volume Stanford Historic Houses books brings us historical and architectural insights into many historic campus houses. The Society’s annual Historic House and Gardens Tours, which are part of the Stanford Historical Society Historic Houses Project, have provided a wonderful service allowing members and their friends to visit the interiors and gardens of many of the best residences described in detail in the six volumes. I won’t try to reiterate the extensive information contained in these extensively researched books and will merely suggest that, if you’re interested in doing an in-depth exploration of many of the houses you’ll pass on this chapter’s walk, you’ll need to purchase these books (volumes I and II are now out of print) from the Stanford Historical Society. Their website is histsoc.stanford.edu. However, I didn’t want my readers to miss the opportunity of seeing, at least from a distance, some of the best residences on the Stanford campus.

Secondly, I worry that some folks following the route of this chapter will walk up driveways or in other ways encroach upon the residences. SO, PLEASE DON’T! I admonish y’all to respect each owner’s privacy. Gander at each house and grounds from the street or sidewalk only! Please don’t even step into the grounds to get a better view or take a closer photograph. The university, the Historical Society, and I are all hoping (and insisting) that you follow this prohibition.

This chapter is divided into three sections. First, I’ll relate some history regarding campus residential development. Second, I’ll describe who is qualified to buy or lease a residence located on land owned by the university (which all of it is). Lastly, I’ll take you on a walking tour of some of the best campus residential areas, much of it jokingly dubbed the “Faculty Ghetto.”

To understand the residential development on campus, we have to go back to 1876 when Leland Stanford initially purchased the 650-acre Mayfield Grange (generally, the area occupied by today’s Stanford Shopping Center) for a stock farm; hence, the moniker now often attached to the university, “the Farm” (and to the name of this book). Over the next ten years, he purchased adjacent farms which included orchards, vineyards, pastures, and facilities for horses (his hobby and passion), bringing the total up to today’s 8,180 acres of contiguous property. One of these acquisitions was a dairy farm owned by Jean-Baptiste Paulin Caperon roughly bounded by current-day Page Mill Road, Galvez Street, El Camino Real, and I-280. Caperon was called “The Frenchman” (thus, the campus’s residential street called Frenchman’s Road), although he usually used the name of his deceased cousin, Peter Coutts; hence, today’s Peter Coutts Circle and Peter Coutts Road, which are located between Stanford Avenue and Page Mill Expressway.

The first ten houses for faculty were built in 1891 on Alvarado Avenue, but their architectural style was a far cry from the grandeur of the residences on today’s Alvarado Row and San Juan Hill. Those initial houses were, all alike, of clapboard (I don’t know what it is but it sounds cheap) construction and built in less than three months. The avenue had no shrubs or grass, nor sidewalk or pavement. No, we can’t see these first residence—the last of them was demolished in 1972 for construction of a parking lot for the Law School.

Leland and Mrs. Stanford’s 1885 original Founding Grant provided that none of the land included in the original gift could ever be sold. However, an amendment in 1902 by Mrs. Stanford, nine years after her husband’s death, allowed the sale of the more remote Vina and Gridley Ranches. Nonetheless, it did provide that the Palo Alto farm and the Stanford San Francisco mansion be retained by the university. To further clarify the rights of the university, also in 1902, a petition from the Stanford Trustees to Santa Clara County verified the legality of all titles for the university’s endowment, thus, superseding the previous grant and its amendments.

The fortunate result of all this is that the university has retained all of the gifted 8,180 acres, including the land on which all on-campus residences have been built. Besides owning all the residential land, the university owns the land on which the world-class Stanford Research Park, the Stanford Shopping Center, and other ultra-valuable properties have been built.

So, in order to provide housing for faculty, a program was created wherein someone who qualifies as an Eligible Person and wishes to own their own home could lease the land from the university on a long-term land lease at a “reasonable” land rent. Thus, houses could be built, owned, financed, and sold subject to the land lease. This program continues today. The land leases are “rolled over” for each subsequent homeowner with corresponding changes in terms and the lease termination date.

So, who’s an Eligible Person? The qualifications are more detailed than I’d think useful to cover here, but, generally, unless you’re tenured faculty employed more than 50% of the time, a Medical Center Professional, a Senior Staff person employed 100% of the time, a Clinical Educator, or “Hoover Institute Senior Fellow,” you’ll not qualify. The list doesn’t even include eight-figure donors! For the entire list of additional requirements, I suggest you go online to fsh.stanford.edu/home-buyers/eligibility.

Prices for residences vary considerably. Most of the snazzier houses you’ll walk by on this loop will be in the $2 million plus range (and, remember that’s for the improvements only, the land is leased) with rentals varying roughly between $4,000 and $9,000 per month. Less grandiose campus houses will naturally sell or lease for less.

Most of the houses you’ll pass on this walk were built during the first half of the twentieth century and, as a result, have been remodeled, some extensively and several times.

The Walk

Now, at last, let’s get going. Walk through Parking Lot A toward the Main Quad away from Mayfield to Lagunita Drive, which adjoins the parking lot. Cross Lagunita, turn left on the sidewalk and walk a dozen steps past the Faculty Club, then turn right into the next driveway, where you’ll encounter nicely landscaped grounds and a large three-story “house.” This is Kingscote Gardens, (#1 on map) which an article in Stanford Magazine dubbed “Stanford’s Own Mystery House.” However, about the time my book was headed for layout and design, I happened to walk by Kingscote and found the grounds fenced-in, the entry driveways closed-off with gates, and plywood nailed over the doors. Upon checking this out, I discovered that Kingscote was no longer to be used for housing and was being converted into offices. I decided to keep it in this chapter anyhow because of its onceillustrious history as a residence. Kingscote was opened in fall of 1917 to house visiting professors and others associated with the university (hence, it’s actually an apartment house, not a single-family residence, but I wanted you to see it anyhow). Over the years its residents have come to include writers, students, and even visiting politicians. The first tenants paid $25 per month. It once was considered a ghost house due to spooky noises coming from the depths of the building. An investigation initiated by the residents discovered the sound resulted from two young female residents joy-riding in the dumb waiters.

Its most famous tenant was Alexander Kerensky, who had been the Russian Premier for several months during the 1917 Russian Revolution prior to being exiled. As an old man, he came to Stanford in 1955 to do cataloguing work with the Hoover Institution’s Russia archives. In 1965, he taught a popular seminar at the end of which students visited Kingscote to read their papers to him because he was nearly blind.

If the conversion has been completed at the time you do this walk, I hope the beautiful grounds will be open so that you may walk around the building to admire it and its landscaping. Exit on its far side onto Lomita Drive. Turn left and walk along Lomita, past its intersections with Lagunita Drive and Mayfield Avenue, uphill to where Lomita Court branches to the right. Take the Court and on your left you’ll next visit The Knoll. (#2 on map)

The site was once a graveyard prior to the founding of the university, but in 1908 a student prank exposed a grave, so the cemetery was moved.

The Knoll, built in 1918, was originally called the President’s House, and its initial resident was Ray Lyman Wilbur, Stanford’s third president, and his family. The reinforced concrete Spanish-revival style building has exterior walls plastered in pink combed stucco. Servants’ quarters were on the ground floor. The top two floors were used by the family. It was planned to be large enough for university functions and guests, and, as simple family residences go, it certainly looks large enough to hold an army of guests at one time. Upon President Wilbur’s retirement in 1943, the next president, Donald Tresidder, elected not to live in the massive house, so a variety of occupants followed. During World War II, a unit of the Women’s Army Corps was quartered there, and after the war the Geography Department used it for a short time. The next occupant was the newly formed Music Department, who used it for offices, classrooms, a library, and practice rooms. When the Music Department moved into the Braun Music building in 1986, The Knoll became the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA). In 2005, the building was renovated in order to incorporate the latest technical advances for CCRMA, as well as seismic strengthening.

This is the one building on this walk that you can enter. For you fans of electronic music, you’ll enjoy seeing the world’s first synthesizer, developed here at Stanford, on display in the lobby. Perhaps other parts of the building will be open, so you can visit some of the sound studios. True, The Knoll is no longer a house, but I wanted to include it in this walk because of its history and grandeur. I like to stand on Lomita Drive down in front of the building to admire it and its grounds from a distance. Its original landscape architect was John McLaren, who also designed Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

From the front of The Knoll, walk back down Lomita Drive past where Lomita Court splits off, and retrace your steps to Mayfield Avenue. Turn right on Mayfield, and walk past the parking lot on your left (where you, hopefully, found a parking space). Continue on Mayfield as it makes a sharp right turn. Here, in the old-days, was the start of Fraternity Row (#3 on map), which was lined with fraternity houses as it proceeded uphill. Walk C-17 describes old fraternity row the way it was 60 years ago before the core of campus was expanded with new buildings and Campus Drive was constructed in the 1970s through the middle of the Row, bisecting Mayfield. After all sororities were discontinued at Stanford in 1944, the sorority houses were converted into non-sorority women’s housing. Today, few Mayfield houses are still occupied by fraternities or subsequently re-admitted sororities.

Although the first sororities appeared on campus in 1894, they were disbanded because of the excessive competition between sorority women and non-sorority women, which had, the trustees believed, led to “serious disunity.” (The oft-stated story that they were discontinued when two women committed suicide because they didn’t get into a sorority is untrue.) The fraternities escaped closure, but the trustees’ displeasure with rushing and pledging activities continued. Most of the remaining row houses have been modified and updated over the years.

You’ll quickly reach Mayfield’s intersection with Campus Drive East. Turn left on it. (You’ll return to this intersection later after doing a big loop.) After walking a couple of blocks on Campus Drive, you’ll encounter Alvarado Row onto which you need to make a right turn. It’s called a “Row” rather than a street because of the earlier mentioned clapboard houses, which were neatly lined up in a row.

I won’t try to describe the many outstanding houses you’ll pass on both sides of the street along Alvarado Row (#4 on map). The older, larger ones not only housed a faculty member but several students as well. Take your time along Alvarado Row so that you can enjoy the varied architectural features of the many outstanding houses. Continue on Alvarado Row as it makes a gentle left curve, then a wide right curve dead-ending one-half mile from

Campus Drive at Mayfield. Turn right on Mayfield, and head back toward the Quad until the next major intersection with Frenchman’s Road. Turn left onto it, and continue for one block past where Gerona Road splits off. Whoa! Here, on your left, at 737 Frenchman is the Frank Lloyd Wright designed Hanna House (#5 on map). I too was disappointed when I first visited 737 to discover that, from the street, only a small amount of the house can be seen, although from across the street the house is a bit more vis ible. Please don’t succumb to your desire to walk up the curving driveway for a better view. It’s “off limits.” I was eventually able to tour the property with a docent provided by the Cantor Center. Public tours visit the grounds and the house’s interior while learning about its interesting history from the docent. You can check the hannahousetours.stanford.edu website to register for Hanna House tours online or by phone (650) 725-8352.

In 1935 the Hannas, who were both special ists in childhood education, asked Wright, whom they knew, to design a house for them and their three children that could be built on a small budget. When Wright produced his first set of plans for the house, it was designed for a flat parcel because the Hannas hadn’t yet picked out a site on land leased from the university. However, the site they chose on Coronado Avenue (now French man’s Road) was on a hill. So, the plans were redrawn using retaining walls and cut-and-fill to nestle the house into the hillside together with its outdoor terraces.

Wright’s design utilized a concrete slab and thin redwood sandwich-wall construction. The architect’s unconventional plans were patterned after a honeycomb, creating a geometric hexagon pattern. As a result, the corners of rooms are at 120° angles rather than right angles. The interior’s hexagonal design allows many of the rooms to be open to one another without doors. The then unique layout allowed large areas of glass and a rigid roof structure, giving the impression that the roof is supported on thin folding screens.

The walls were prefabricated and assembled by carpenters on site, then tilted up, screwed together, and bolted to the floor. Many of the thin shoji-like window-walls open onto outdoor patios. Construction of the house, whose unusual design made calculations on accurate building cost con tainment almost impossible, took most of 1937.

In 1975 the Hannas gave the house to the uni versity. It was then the residence of four succes sive Stanford provosts until the 1989 earthquake, whereupon it was immediately vacated. The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake unfortunately caused extensive damage to the Hanna house. The unre inforced chimneys shifted, and significant other damage occurred due to inadequate reinforcing, poor design of connections, and insufficient soil compaction causing the floor slab to crack and dis locate. The building was in danger of completely collapsing had there been further earth shaking.

Wooden frameworks and bracing buttresses were quickly built to prevent additional damage. The house remained unoccupied for many years because university funds for its restoration were diverted to higher priority project on the earth quake ravaged campus. Because the house was ill suited for residential use due to its small number of rooms, minimal privacy due to its open design, and difficult spaces for conventional furnishing, the Hanna House Board, which oversaw the house, decided it should be used for non-residential pur poses. The decision was made to restore the home as closely as possible to the way it was toward the end of the Hanna’s occupancy.

In 1991, a group of specialists was hired to make recommendations on rehabilitation plan ning in conformance with building codes and seismic upgrading. Preservationists complained that the end result would significantly deviate from Wright’s original design, thus, making the house merely a replica. Other plans were cast aside that involved steel beam bracing, much of which would become visible. At last, a consensus was reached in a document presented to the Board in July 1995, which included the needed upgrades but allowed the design to remain true to its condition prior to the earthquake. The cost of doing this work was expected to be $1,300,000, excluding all needed furnishings. Completion of the restoration work, which totaled nearly $2,000,000 by the end, took almost ten years from the time the earthquake occurred. It reopened in April 1999 as a place for Stanford conferences and receptions, although due to the size of the house it seems to me that those must be rather small conferences or recep tions. I hope you’ll be able to join a tour of the house some day.

As long as you’re on Frenchman Road, you might want to walk a short distance down French man to look at 781 (from the street only, of course), called the Mazour House (#6 on map). It is described as an example of what architects call “the Bay Area style” due to its vertical board siding, sloping flat roofs, and closed front elevation.

Now, backtrack on Frenchman to where Gerona Road cuts back sharply to your left. Take Gerona and very soon you’ll find Mirada Avenue turning right off Gerona and heading uphill.

Along here are some exquisite houses (not that those you’ve gone by in the past 15 minutes have been shabby). Of particular noteworthiness is 669 Mirada (#7 on map), which began life as a small 1,686 square foot two-bedroom, one-bath cottage in 1920. It went through several remodels, but, in 1969, the present 6,400 square foot house was built on a new foun dation. Volume V of Stanford Historical Society’s marvelous Historic Houses series describes many of the houses along Mirada in this Southeast San Juan neighborhood, so I won’t attempt to elabo rate on the book’s extensive research. (I’ll again remind you what the Historical Society implores: please don’t trespass.)

As you approach the top of San Juan Hill, where Mirada becomes a circle around the hilltop, turn right, and in a few steps you’ll witness the unique Lou Henry Hoover house (#8 on map)on your right. Conceived during World War I and built in 1919, it was initially the home of then Stanford Trustee, Herbert Hoover (class of 1895) and his wife Lou Henry (class of 1898). Mrs. Hoover was instrumental in selecting Stanford Art Department Chair Arthur B. Clark and his archi tect son, Birge, to design the house. As you’ll see, their plan was inspired by Moorish architecture. It continued to be the home of the Hoovers after his election to U.S. President in November 1928 and for many years thereafter. Upon the death of Lou Henry in 1944, the former U.S. president gave the house to Stanford, and, thereafter, it has been used as the main residence of all succeeding presidents of the university. In 1985 it became listed as a National Historic Landmark. The house is still occupied,so please stay on the corner and don’t wander around the building.

After admiring the Lou Henry Hoover House, continue along Mirada, exiting the circle by turn ing right at the next corner. Walk one-half block to a T intersection with Santa Ynez Street, onto which I suggest making a right turn. Santa Ynez curves right around the hilltop. Both Volumes I and III of the Historic Houses books describe in detail houses along this part of your walk.

After walking past several exquisite houses on both sides of the street, you’ll notice that Santa Ynez makes a 90 left turn. Your route, however, continues straight for another block on Cabrillo Avenue. One block later, turn left on Dolores Street. You’re now off San Juan Hill. In two short blocks, Dolores will end at Mayfield Avenue, onto which a left turn will lead you back toward the main part of the campus. Along here on your left are houses that were part of old Fraternity Row, mentioned earlier.

Just before you get to the next intersection with Santa Ynez, notice on your right some smaller cute houses at 625, 619, 615 and 607. These were originally part of an eight-house cluster called the

Hoover Cottages (#9 on map). Lou Henry Hoover, wife of Herbert Hoover, recognized that only large fancy houses were being built for faculty. So, she pro posed building smaller cottage style houses that were more affordable for faculty members. The first five were built in 1924–25 with the remaining three following a year later. All were two-bedroom one-story cottages with red tile roofs and stucco walls, thus, resembling a Spanish village. As with most other houses you’ve passed on this walk, the Hoover Cottages have been enlarged and modified from their original configuration.

Keep moving along Mayfield until you reach the corner of Campus Drive where you were an hour ago. Cross Campus Drive, then turn right and, shortly thereafter, left onto O’Connor Lane. Soon, on your left, you’ll encounter the Griffin Drell House (#10 on map) that a 2005 Stanford Magazine arti cle described as Queen Anne style with its twin rounded towers. It dates from 1892 and was origi nally located at 570 Alvarado Row, being the 12th residence constructed along what was then called Faculty Row. The attractive house was featured on early campus postcards. When Campus Drive was built in the 1970s, the Griffin-Drell house was in the path-of-progress so was uprooted and moved to its present location.

You’re now close to the end of your outing, so continue a few more steps on O’Connor past Owen House, then left onto a walkway between Owen and Columbae House that intersects with Lasuen Mall. Here you’ll be back to the corner where Mayfield makes a sharp right turn. Park ing Lot A is just ahead on Mayfield.

The Historical Society’s Historic Houses Volumes II, IV, and VI describe houses along this part of your walk. Today’s Mayfield was originally named Lasuen Street and, as mentioned earlier, was dubbed Fraternity Row. When Campus Drive East was built in the 1970s, it bisected Mayfield. Many of the old fraternity and women’s row houses have been demolished, moved elsewhere, or converted into “theme” residences whose vari ous names you’ll pass as you proceed on Mayfield. Walk C-17 (in the book) describes old fraternity row the way it was 60 years ago. Beyond Campus Drive, you’ll be retracing a short portion of Mayfield on which you were an hour ago. Parking Lot A is just around the bend on Mayfield.